How Do I Make Breaking Changes in Go Without Annoying People?

Knowing when and how to make breaking changes is tough. It is even tougher in the Go ecosystem. After being burned by making a breaking change and annoying people, I’m going to investigate how best to mitigate this annoyance.

Disclaimer: This is mostly opinion, and only my opinion. This post is not associated with my employer in any way. You can contact me on Mastodon @kn100@fosstodon.org

What even is a breaking change, anyway

A simple definition of a breaking change is any change you make to your code that could break other code which directly or indirectly depends on it.

In all seriousness, almost anything you do within a Go library that others depend on could be considered a breaking change. Did your commits fix a bug that was reported, without changing the API? It’s possible there is code out there that was depending on the presence of that bug, and you’ve just broken their code. Did you update a dependency you depend on? Did your dependency fix a bug consumers of your library were depending on? You get the point.

For the purposes of this article, I align my definition of a breaking change closely with the one given by Semver.org, which is any “incompatible API change”. The key word there is API. This (to me at least) indicates that bug fixes or similar would be considered patch or minor version updates. If you anticipate that you’ll break someones code through changing your API, that’s a major version increment. Otherwise, it’s a minor or patch. The clue is in the word “semantic”. A Semver number is intended to be read by humans, not computers. This does not guarantee that a minor version increment is going to be absolutely fine for everyone. Those edge cases where consumers rely on the presence of a bug are difficult to anticipate and therefore are not considered here. The more significant an increment, the more trouble the user is likely to have when upgrading.

A story on making a breaking change

I maintain a library that is written in Golang. It’s a pretty standard library, and has a pretty simple API associated with it, maybe 7-8 functions that consumers can call. Nothing specialist. It was a library that had some small design issues as well as old code that was now dead. I’d been planning to make a breaking change in the API for a few months, and waiting for an opportune time to do it. In total there were 3 distinct breaking changes I wanted to make, only one of which was really ‘required’, the others were stylistic/linter improvements that I wanted to make.

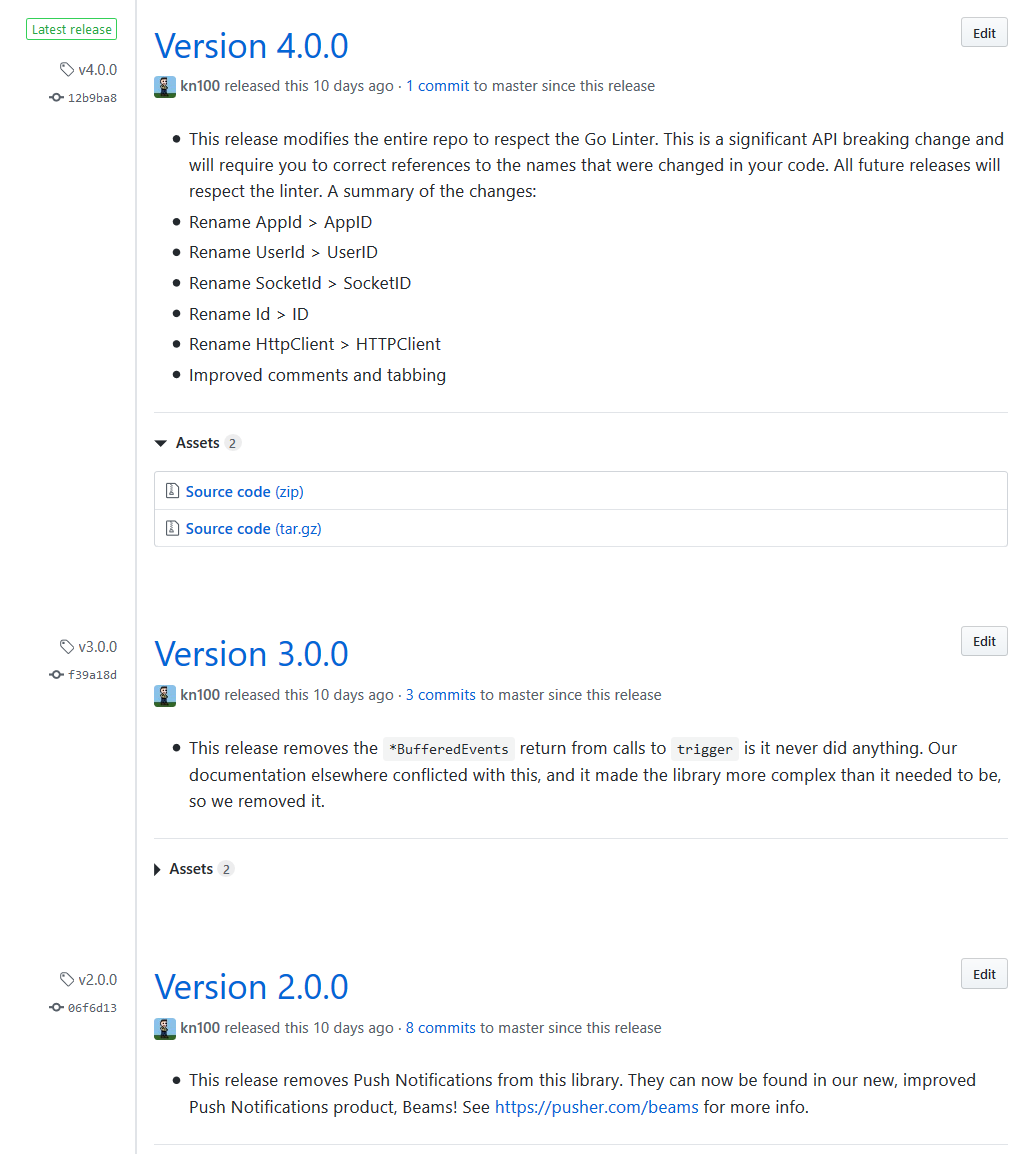

I made three separate pull requests, had them approved by others who maintain said library, and made three separate releases on the same day, bumping the ‘major’ version number three times on the same day. I respect that these could have all been rolled into one major version bump, but I personally did not see the harm in incrementing the major version. This looked a little ridiculous, but my thinking was that this would allow users to upgrade incrementally, rather than having to deal with 3 conceptually different breaking changes in one go.

The releases page on Github looks a bit ridiculous.

I thought this was enough to indicate that changes had taken place. I tried to describe exactly the changes that were made - and give clear instructions as to what to do to migrate up to that version.

What I had of course forgotten about is that Go ideally does not expect you to ever make breaking changes. A few of the libraries consumers rightly complained about the breaking changes, which is what inspired this article.

“You changed AppId to AppID and also UserId to UserID and it took me hours to figure out why my deployments weren’t working. Come on guys lets not introduce breaking changes like this without some sort of heads up!”

Go get - somewhat flawed

In the very early stages of development, when a consumer of a library wishes to consume it, they’ll usually use go get, a tool which requires basically no thought to use. It will fetch whatever is on master at that point. Not what you’ve released, and not whatever is on a release branch. go get is pretty much git clone, with Go tendencies.

The consumer will then eventually run go build or go run and their software will build and run as normal, even if the library author makes a breaking change. The Built binary is, well, built, so it will be fine. The developers build environment will be fine since it effectively vendors the library code - and won’t update it unless asked. If the user dares do a go get -u on the package, or recreates their build environment locally, they’ll receive the breaking changes, and therefore will have to deal with them.

The trouble starts when that consumer then either tries to build their code on another machine. The consumer go gets the packages they need again, except now there has been a slew of commits merged into libraries master branch, therefore inexplicably breaking their build.

The user then spends a few minutes trying to figure out why what works on their machine does not work in their CI environment, or on their AWS instance, or in their Docker container. Eventually, they find log lines that indicate a variable has been renamed, or a functions return type has changed, or the function they were using is gone altogether!

Frustrated, they either stop using your library, or they contact you and ask why you made such a change.

This whole process was designed by Google, for Google. It was designed for how they manage their repositories. Of course, other organizations manage their source code differently, and conflicts were bound to happen. This lack of package management meant that breaking changes rendered once fine builds completely broken. In other languages where package management has been a first class citizen for longer - this is not an issue, but in Go, it is. No amount of Semver is going to dig us out of this hole.

The fundamental problem with Go Package Management

I am not going to talk too much about the state of package management in Go. Enough has been said on that topic already. What I will say is none of them really address this problem. Not really. It doesn’t matter how good your package manager is. It makes no difference whether it vendors your dependencies. It is not the default, and therefore breaking changes are going to break someones code.

Since anybody writing go today isn’t likely to want to think about the intricacies of dependency management immediately, and it is certain that there are projects everywhere that do not use a package manager, it is crucial to consider the various factors that weigh into whether a breaking change is worth it or not.

The problem is that you are going to have consumers who are going to consume your code and expect there to never be a breaking change. This is the unchangeable reality of Go.

Are breaking changes possible then? This is a question that only the owners of the library can answer. How many consumers do you have? Does the benefit of making the breaking change outweigh the almost certain annoyance your consumers will face? Are there ways of making the change without breaking the build? Do you have a mechanism to warn users that breaking changes are coming? The factors which weigh in are numerous and each should be considered.

So, How DO I make breaking changes

There are many approaches to making breaking changes in Go. This is part of the problem. Without unifying our approach as library maintainers, we’ll struggle. I have no idea what the correct approach should be, and there are more than are listed below, but I hope this brief survey will be useful when you make your decision as to how to do it.

Just never making breaking changes ever

This is the only real solution. If not annoying users is your absolute top priority, then never make breaking changes! Design your API upfront to be as close to perfect as possible, and only ever add code that does not change the API.

This is the approach that many crucial components of software take. Only ever add functionality, never take it away or change existing functionality. Never break the build. This approach ensures you’ll annoy the fewest people, but of course has the disadvantage that you’re unable to fix any mistakes in your original spec.

Branch off for breaking changes

Another approach that some libraries take is to maintain version branches. For example, see github.com/robfig/cron. Here we can see there is a master branch which I assume v0, and then branches for each breaking change. I expect that the idea is that a user who wants to ensure their code will build forever will move to the directory where Go checked out the code, and then move to the branch that their code is written to support.

This ensures that (as long as the library author keeps their promises!) users who remember to check out the correct branch can expect their builds to continue working and their code to continue working.

This has the same downside that users do not have an obvious way to know how to move up major versions, and puts the onus completely on them to determine if there has been a major version update. If they decide to update major versions on one build machine, they must then follow suit everywhere else. This isn’t great.

Somehow notifying consumers of breaking changes

I’ve heard suggestions that maybe library authors should notify consumers about upcoming breaking changes. One approach is to release a version of your library where you log out that a given thing is changing on a certain date, and on that date release the next version which actually removes or modifies said functionality. This approach relies on the user consulting their logs frequently for these notices - something I’m not particularly hopeful happens. I expect most developers including myself only ever really consult logs when things go wrong, and here they go wrong when the thing is changed, meaning the log lines helped nobody. Semver seems to advocate for this approach, suggesting that we “issue a new minor release with the deprecation in place”. What form this deprecation takes however is left undefined.

Another suggestion I heard from other developers was to somehow contact the consumers of the library to inform them that the breaking change is coming. For instance, users who care about breaking changes could sign up to a mailing list. Maybe you have a method of identifying and contacting consumers already. Then, when you anticipate a breaking change, you contact the customer via email or something to let them know. This approach has a similar problem to the first, which is that I expect people signing up to said mailing list would only do so as a reaction, rather than proactively. Contacting your consumers with emails you’ve already got somewhere else somewhat solves this, but will users really read this email? Will they action it? Will they even realize that the change affects them?

Declaration that breaking changes are to be expected

Given that almost every library that is not already well defined is likely to want to change its API at some point, I think the most realistic approach we’ve got is to explicitly declare that breaking changes are to be expected in the README. Something along the lines of:

This library, and any others that you are using, may make breaking changes at any time. These changes could unexpectedly break your build. To avoid this, we recommend you use a package manager such as the inbuilt Go Modules, a tutorial for which can be found here.

This is clearly not perfect. This requires your consumers to take action and do something in order to prevent this problem in the future - however I think it is fairly reasonable. If we look at other examples of how this problem is handled in other languages, we’d see that libraries sometimes even include a snippet to copy into the Gradle file or the language itself will write a package lock file that locks to whatever the latest version was at the time of installation.

This does however point Go consumers in the correct direction for safely using their libraries, and even better, thanks to the way Go modules works, even solves the problem automatically for other libraries that are installed! This doesn’t solve the problem at all for consumers that will not or cannot use a package manager, so this, in use with a commitment to make breaking changes as infrequently as possible seems like a solution that will annoy the fewest people over time.

In my humble opinion, use of a package manager should become the norm. Bare go get should be discouraged for everything except experimentation. I have been bitten by others making API breaking changes and I personally have inflicted that pain on others. It’s an easy thing to miss - and there are many situations where using a package manager isn’t ideal - but in a world where breaking changes are going to be made, pretending that they’re not going to be is not a solution.

Go mod has its own idiosyncrasies, but it’s as close to a built in package manager Go has gotten so far. I think it’s worth it in the long run for libraries to encourage its use and to make it the new normal for developers just starting out in Go. The thousands of unbuildable projects floating around that have depended on libraries that broke backwards compatibility will look on and smile.

Let me know what you thought! Hit me up on Mastodon at @kn100@fosstodon.org.